One of America’s iconic film critics, the late Pauline Kael had described the role of a Film Critic as someone “who helps people see what is in the work, what is in it that shouldn’t be, what is not in it that should be. He is a good critic if he helps people understand more about the work than they could see for themselves. He is a great critic if, by his understanding and feeling for the work and by his passion, excite people so that they want to experience, more of the art that is there, waiting to be seized. He is not necessarily a bad critic if he makes errors in judgement. He is a bad critic if he fails to awaken the curiosity, enlarge the interest and understanding of his audience. The art of the critic, hence, is to transmit his knowledge of and enthusiasm for art to others.”

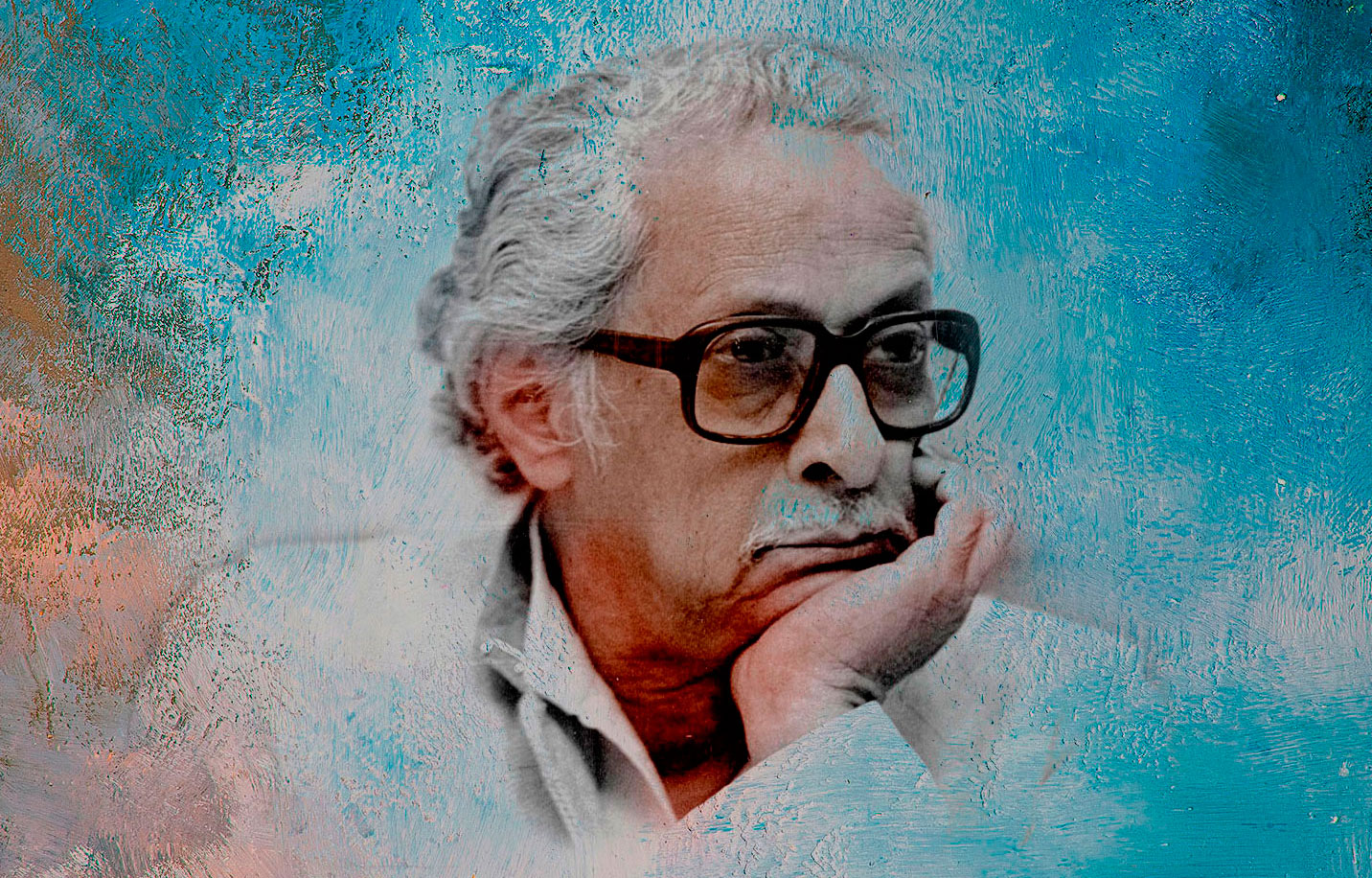

It is uncanny how this description so aptly fits Dasgupta. A co-founder, along with Satyajit Ray and a few other film buffs, of the Calcutta Film Society in 1947 and the Federation of Film Societies in 1960, he played a major role in initiating a new movement towards the creation & appreciation of a new brand of cinema in post-independent India. His columns in various newspapers and publications as well as his books placed him as THE DADA OF FILM CRITICS, as columnist and film critic Shubhra Gupta had once famously pronounced,. His films and documentaries only re-enforced his image as a dynamic thought-leader who viewed cinema as a powerful agent of change.

However, Dasgupta’s unique and enduring contribution lies in what he brought to the table while mentoring future critics. This found real expression during the time he was the Arts Editor of The Telegraph during the late 80’s and early 90’s. He proved himself to be one-of-a-kind because he brought civility combined with wit and wisdom to the art of film criticism. While he did not mince words, his material was marked by a generosity of spirit and a lightness of touch. He had exceptional breadth of vision. Erudition sat lightly on him. These qualities rubbed off on those he mentored and worked with. His knowledge and interests were not confined to cinema alone. His perspective was all encompassing, embracing society, politics and culture into the sweep of his work. He was a very gentle as well as a ‘genteel’ mentor, treating everyone as an equal. He never imposed; he only suggested. It is because of him that serious film criticism and studies came of age in India. He showed that critiquing did not mean shredding; it meant understanding and analysing the film/art form in the larger context of the time it was made in.